The city of Gdańsk has a historical centre with several striking buildings which can make any historian’s heart beat faster, even with the knowledge that they were partly rebuilt after the destructions of World War II. Most interesting from the perspective of early technology and industry are the magnificent fifteenth-century Crane along the River Motława, which also functioned as a gate, and the, probably lesser known, Great Mill. The latter, the largest mill in northern Europe in the pre-modern period, was built in the second half of the fourteenth century, some time before 1364. It was rebuilt as a larger building in brick after a fire around 1391, after which it began to be referred to as the Great Mill. Before 1471 it was extended in length to allow for more wheels to be added. The mill was located on an island in the Radunia canal, also referred to as the Mühlgraben – mill ditch, which not only moved the wheels of the Great Mill, but also those of other mills located there, such as a sawmill and a cutting mill. The canal also supplied the town with clean drinking water.

At the time of the mill’s construction Gdańsk, then commonly referred to as Danzig, consisted of three administratively separate settlements under the lordship of the Knights of the Teutonic Order. This changed in 1454 when the town asked the Polish king to help it dispose of its lords to become a united and largely autonomous city under his lordship. The king agreed and granted far-reaching privileges in 1457. It took thirteen years of war (1454-1466), however, before the Order gave up its rights to the city and to what was to become Royal Prussia.

The Great Mill, which had been built at the behest of the Knights, had been seized by the citizens of the city on the day after their denunciation of loyalty in February of 1454, thus depriving the Order of one of its largest sources of income. The town council had been unhappy about the high fees charged at the mill for decades, and taking over lordship of the mill was probably high on the list of priorities at the time. As soon as the mill was confiscated, the supply of meal and malt to the castle of the Order’s governor (Komtür) was halted. During the subsequent war the water supply was cut off on a number of occasions, which prevented the wheels from turning. But the benefits of lordship over the mill clearly outweighed these setbacks, and it remained firmly in the hands of the city. Interestingly, the town council did not subsequently lower the fees for milling: it continued to be 1/16th of the value of the grain to be ground.

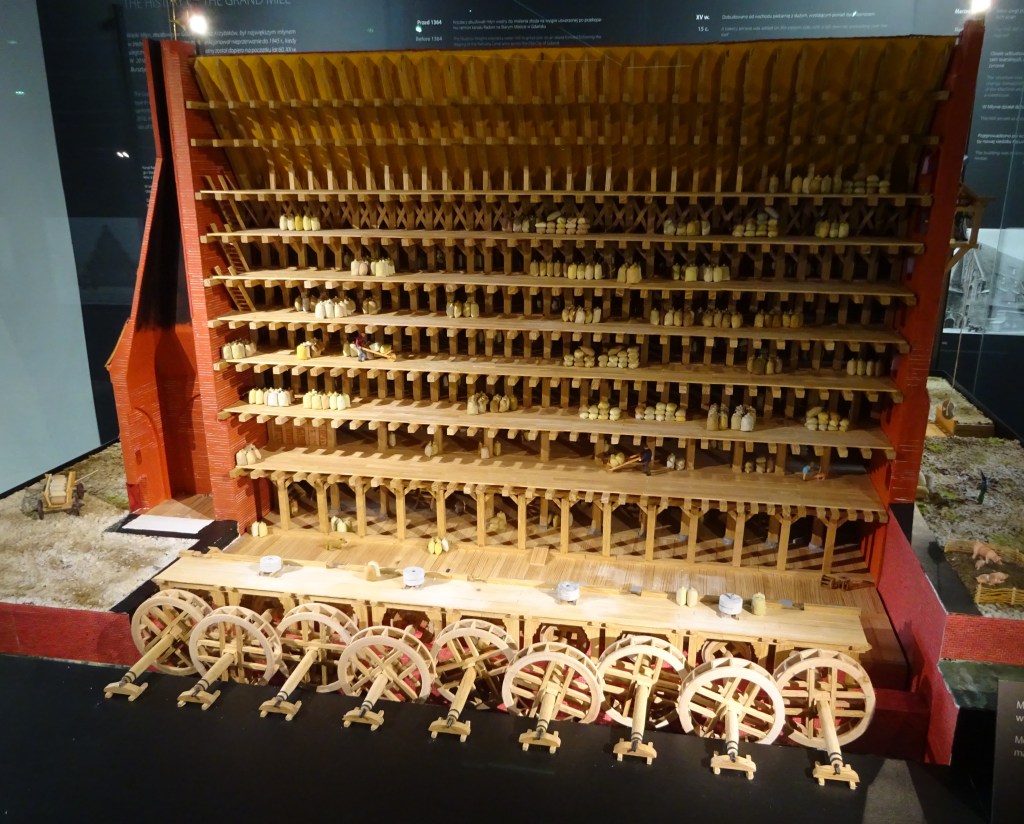

The Great Mill initially had twelve water wheels, but six more were added to reach a total of eighteen (nine on either side) when the building was enlarged sometime before 1481. The existence of such a large mill at this time suggests that the Teutonic Order had a lot of grain to grind, and that this amount increased even further in the second half of the fifteenth century. It has been estimated that Danzig had about 20,000 inhabitants in the mid-fifteenth century, making it one of the largest cities in northern Europe. Even so, it is unlikely that a mill with twelve or eighteen wheels was used only to grind for the city itself. Some of the meal and malt must have been earmarked for export. Of course, Danzig is known as the granary of Europe, but this title refers to the export of rye to western Europe which only really took off in the sixteenth century. Unfortunately, sources for the fourteenth and most of the fifteenth century are lacking, so that it is difficult to gauge exactly where the meal and malt ground by these eighteen wheels went. Christina Link has argued that, as opposed to grain which mainly went west, meal was transported east and north.

That Danzig had a certain reputation for its milling expertise across the Baltic is suggested by a couple of letters from the late fifteenth century, which provided the incentive for writing this post. In June 1491, Sten Sture, governor of Sweden, sent a letter to Danzig about a number of topics, especially the hardship experienced in the town of Åbo (in Finland; Turku in Finnish) as a result of the high price of rye: ‘wente ick was in dem vorghanghen wynther in Fynlandt unde sach, dat dar harde tydt was myt rogghenn’. Scarcity and high prices were a Europe-wide problem in the early 1490s. Towards the end of the letter, Sture related that he had hired a man from Rügenwalde (now Darłowo in Poland) to build a mill in the ‘stream before the castle’ in Stockholm. This builder had already started the process of building by sinking some chests and by driving poles into the riverbed when he died unexpectedly. Seeing that money had already been invested (and presumably also because it would be useful to have a mill), Sture was now looking for someone to complete the building. He had heard that there was a man in Danzig called master Peter who knew his way around mills (‘ick erfare, dat eyn myt juu genomet mester Peter sole wesenn, de sick up sulke dingk wol sole vorstan’). Sture requested to be allowed to borrow this master mill builder, who may well have overseen the extension of the Great Mill some years before, and send him to Stockholm as soon as possible. He would be well paid.

On the 23rd of August, Danzig responded to Sten Sture’s letter. Concerning the request to send master Peter to Stockholm, the letter explained that the master had declined the offer to cross the Baltic for reasons of age and health (‘he mit older vnnde krancheit bestricket sij’) and that he would be unable to complete the work as a result. Danzig concluded by saying that if anyone else came to mind, the request would be passed on. Whether or not Sten Sture found another builder to finish his mill is unknown to me at this time.

These letters suggest that mill-building expertise in the Baltic region was limited. Sten Sture apparently could not find anyone suitable in his own kingdom, and contracted a man from the duchy of Pommerania (which had been linked to Sweden in the past when Duke Erik of Pommerania became king of Denmark, Sweden and Norway between 1397 and 1439) before he got in touch with Danzig to hire its master builder. The fact that Sture had heard about master Peter indicates that knowledge about people with very specialised skills was shared over long distances. It would be interesting to find out more about this master Peter and whether he was involved in building any other mills in the Baltic region.

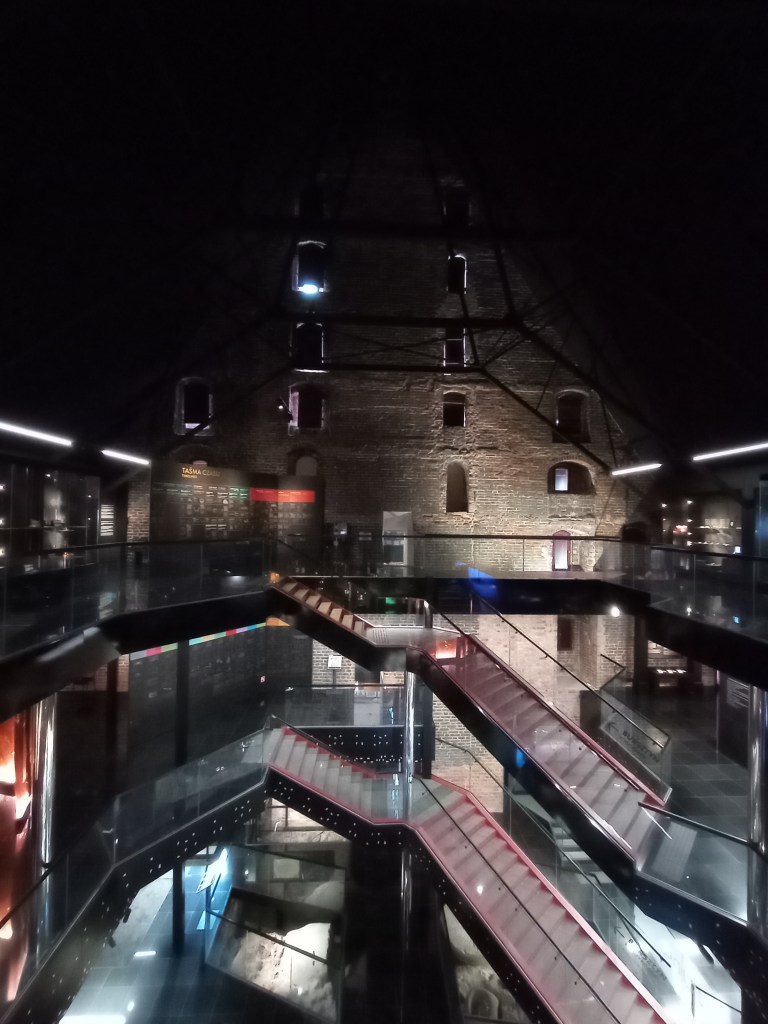

The Great Mill of Danzig with its eighteen wheels continued to function for a long time after this episode, in addition to being used to store large quantities of rye and other grain across six floors. A bakery annexe was also added sometime in the fifteenth century. In 1880 steam turbines took over the grinding and the mill would stay functional until World War II, when it was largely destroyed. The structure was rebuilt in the 1960s and has since had many different functions. During its most recent restoration it was turned into a museum: the Museum of Amber, in which there is also a space dedicated to the building’s history. These restorations have allowed for the citizens of Gdańsk and visitors to continue to admire this building, which stands as a great monument to the city’s role in the grain trade in northern Europe as well as the industriousness of the people of the late medieval period.

Blog post by project researcher Dr Edda Frankot, Utrecht University

All photos taken by Edda.