The next in our series of guest blogs for 2024 which explore issues relating to the grain trade across Europe in the period 1315-1815.

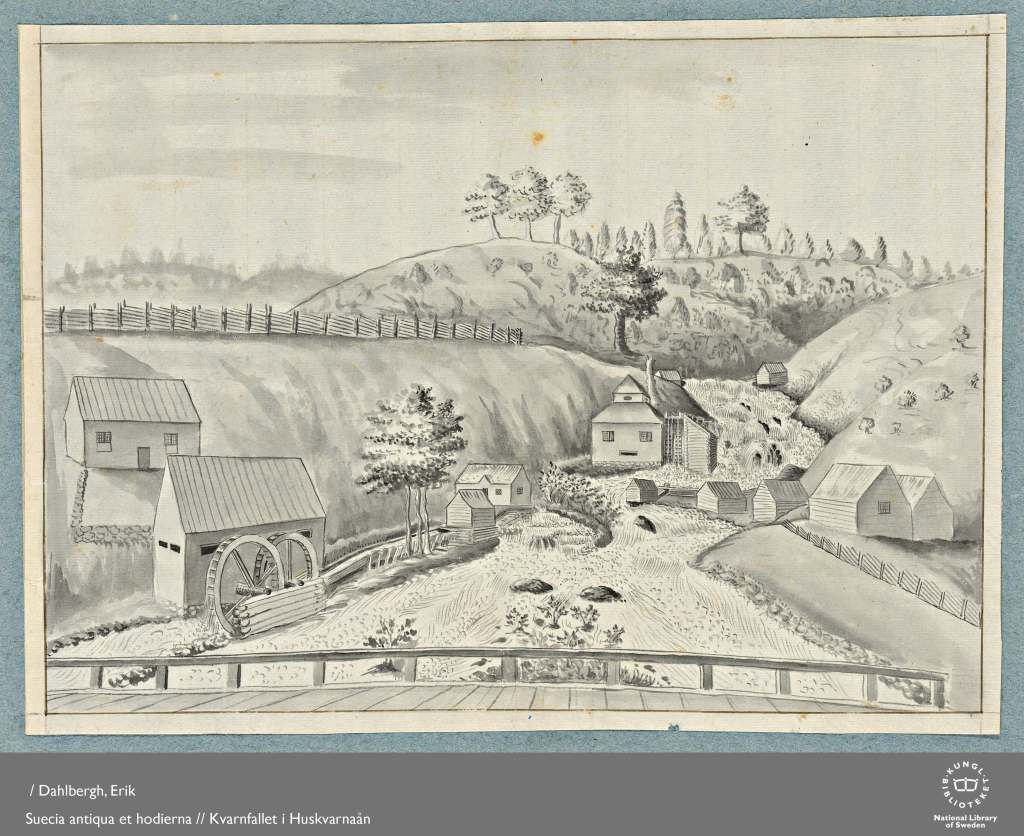

Mills were among the most important infrastructure in Early Modern Europe, as grain – which was the main source of calories for premodern populations – had to be ground before consumption. For this very reason, owning a mill could be a very valuable asset, especially since various institutional measures were put in place to ensure a steady flow of customers. In many parts of Europe, this was ensured by enacting local milling monopolies, through which some villages were forced to use the local mill of the manor. In Sweden however, peasants were usually free to choose whichever mill they wanted. Milling monopolies were instead enacted by severely restricting the construction of new mills in the vicinity of pre-existing mills. This way, de facto local milling monopolies could still arise, as peasants only had access to one mill within travellable distance.

Many of the restrictions on the construction of new mills in Sweden was put in place in the early decades of the 1600s. Over the next two centuries, Sweden’s population almost tripled, with grain production (and imports) also greatly expanding. Yet, the restrictions on mill construction meant that milling capacity did not keep up. In 1825, state commissions produced inventories of all mills in Sweden in order to assess milling capacity in relation to presumed local need. This was not the first time mills had been at the centre of attention in the Early Modern Swedish state. In the 1620s, all mills were registered in order to assess their tax-paying capacity. Seventy years later, another investigation was carried out, this time to see if mills had been built on land or in water belonging to the crown. The documents produced by these commissions may be used to study how local milling monopolies arose during the Early Modern period, and how they affected the country’s milling capacity.

So far, we have carried out a preliminary study of the development in two rural parishes in Western Sweden. In Herrljunga in Västergötland, today located on the main train line between Gothenburg and Stockholm, there was one large water mill owned by a nobleman, which took about 50 per cent of the milling market in 1625, while two small peasant-owned water mills together took about 40 per cent; the rest of the flour in the parish was ground on hand-operated household querns. Seventy years later, according to the commission of 1699, only one of the previous smaller water mills remained in use. During the eighteenth century, this mill was then expanded into a large watermill, which was sold by the crown to its tenant in 1763. In 1819, only the old nobility mill and this new mill (now owned by the parish vicar) remained. The number of mills thus decreased during the two centuries, while milling capacity probably remained largely unchanged, despite a population increase of over 60 per cent. The 1825 report consequently found that the local need for milling capacity was ten times that provided by the mills in Herrljunga.

The situation in Gestad parish, located about 40 miles north-west of Herrljunga on the shore of Vänern, the largest lake in Sweden, was very different in 1625. Here, more than 80 per cent of the grain was processed by peasants on their household querns, the only exceptions being one small peasant-owned water mill and one small windmill. Their capacities were very limited, equivalent to only 2–4 hand querns. Although the commission of 1699 found that the number of small water mills had expanded to six, these were all located at the periphery of the parish, more than 5 miles away from the church. An investigation carried out by the local authorities in 1819 however found that five of the six mills had been demolished already before 1728, and that since then only three small water mills remained in the parish. In 1825 the capacity of these mills was estimated at less than one percent of what the parish population required. Despite the population of Gestad nearly tripling during the two preceding centuries, the number of mills in the parish remained almost constant. This means that either hand querns had become even more dominant in 1825 than they had been back in 1625, or that travel to mills outside the parish had become an ever more costly and time-consuming activity for the parishioners of Gestad.

In the early nineteenth century, there was consequently a dire lack of milling capacity in both parishes, as well as in Sweden as a whole. The reasons behind the lack of mills were however complex. In Herrljunga, it seems as if it were local milling monopolies that curbed the establishment of new mills; milling capacity, which in 1625 had been rather adequate for the needs of the parish, remained largely constant over the following centuries, causing it to fall far behind the population increase. The main benefactor of this development would of course have been the mill proprietors, which in the case of Herrljunga over time shifted from a local noble family to the crown, and then to the parish vicar. In Gestad however, no mills with local monopolies existed. The failure to construct mills in this parish to meet the needs of a rapidly growing population thus has other explanations. Perhaps it was a lack of local capital to invest in mill construction, or perhaps a lack of suitable natural conditions for the construction of water mills. We do not yet know the answer to this question; all we can say is that for the population of nineteenth-century Gestad, this either resulted in very long trips to other parishes to have the grain ground on their mills, or else in countless hours spent by the women of the parish working household querns.

Martin Andersson, Researcher at the Division of Agrarian History, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences

wow!! 21Local Milling Monopolies and the Lack of Milling Capacity in Early Modern Sweden

LikeLike